A mahaffa, I learn, is a handheld fan made by weaving the fronds of palm trees, a ubiquitous household item that is emblematic of Iraq and the Gulf region. It is also one of the few belongings that Hayv Kahraman’s family took with them as they fled to Sweden from Iraq, during the first Gulf War.

In Re-weaving Migrant Inscriptions, Kahraman’s third exhibition at Jack Shainman on West 24th Street, in Chelsea, the mahaffa forms the central motif in new paintings and collages that combine elegant self-portraits in oil paint with intricate geometric patterns formed by plain weaving techniques. The artist’s work embodies an autobiography of mnemonic fragments constructing a narrative of forced exile, displacement and cultural assimilation.

The Kahraman family’s mahaffa, which now resides in the “Iraqi Corner” of their home in Sweden, serves as a testament to their survival as refugees, and to the war-torn and ravaged country that lives on in an altered, mythical dimension. Kahraman’s intimate relationship with it is evidenced in two smaller paintings, “Mahaffa 1” (2017) and “Mahaffa 2” (2017), in which she brandishes the object against her breast while gazing at the viewer. In the first painting she holds it right side up, and in the second she turns it upside down, in the same way we may linger on a precious thing, turning it over, holding it close, to know it deeply.

These are the only two paintings in which we see the actual flag-like form of the mahaffa. Everywhere else, the household object is asserted and reasserted through the warp and weft of linen rendered through precise, surgical cuts that have become one of the artist’s signature improvisations. In two compelling studies (“Study 1” and “Study 2,” both 2017), Kahraman imagines her body as the mahaffa. The looser weave pattern is frayed, blistering and falling apart, unravelling the protagonist in the process.

Kahraman assimilates divergent cross-cultural styles and genres, most notably from the Italian Renaissance and Japanese ukiyo-e prints. The artist, who trained as a graphic designer, confirmed in an interview that a four-year period spent in Italy exposed her to the idealized representations of womanhood by the likes of Botticelli. Later, however, she tells me, it dawned on her that these depictions were “colonized” by the male, Eurocentric gaze, which led her to critique power-hegemonies.

In two miniature collage works, a painted image of the artist’s mouth and tongue are interwoven. If the mouth enables the voice, and the voice is the carrier of personal agency and expressive will, these works invite an allusion to speaking truth to power. The artist first cut into linen as a small act of rebellion against the substrate that has borne centuries of male-gendered perspectives of Western civilization. Immediately, the cut became a reason to repair, to mend.

She took the canvas off the stretcher bars and cut it into strips, which she wove back into the original surface, inventing a palimpsest, an irreversible document of subversively reckoning with the history of art. The implied violence of a sharp cutting-tool making its neat incisions into a material closely synonymous with skin is inescapable, especially when read within the context of the war machine that dispenses with female flesh as easy collateral. The history of art – like the history of war – is the history of power.

In an another recent body of work, Audible Inaudible (2016), exhibited for the first time at The Third Line in Dubai, and again at the Joslyn Museum of Art in Omaha last year, Kahraman introduced sonic foam, a dark gray material used for the absorption of sound. After cutting diagonal crosses into meticulously prepared fine linen, she pushed pyramid-shaped foam through the surface, from the back. These “sonic wounds” were intended to retain the sonic memory of air raid sirens from her childhood.

J. Martin Daughtry, an ethnomusicologist and author of Listening to War, Sound, Music and Survival in Wartime Iraq (2015), writes in the catalogue essay for The Third Line exhibition that war inscribes itself on the body, and while the invisible wounds inflicted by sonic violence during wartime are less obvious, they are no less traumatic. “Sound,” Daughtry writes, “is the most expansive vector through which violence is administered.”

Sounds emulating air raid sirens were played on the phones of female actors during a new performance piece created by Kahraman to accompany the gallery exhibition. Five women of multiracial denominations read from scripts, detailing first-person accounts of the artist’s life in a powerful invocation of a collective bearing witness to personal trauma. If sound is the most expansive vector for violence, then the voice – the one that bears witness – is the most compelling one for justice.

Each testimonial starts with the phrase “Let me share with you my memories” and recalls episodes of war and trauma that span a quarter century, from huddling with family members by candlelight in a dark basement in northern Iraq to the intrinsic need as an expectant mother to connect with her past, in order to transmit familial genealogies and cultural histories to the next generation. In one of her testimonials, Kahraman talks about the peculiarity of her middle-eastern features among fair-skinned and blonde Swedes. “No matter how hard I tried to erase myself, I would always be the other person who carried her native home on her back,” she writes. “I will always be the refugee.”

How does one make sense of interrupted narratives, trajectory lines broken midcourse and re-directed? How does one reconcile with the loss of imagined communities and cultural belonging?

Kahraman, who is ethnically half-Kurdish of Iraqi origin and a naturalized Swede currently domiciled in the US (she lives in Los Angeles), is no stranger to identity politics. Her family was part of one of the largest exoduses of Kurds from Iraq in the 90s; she faced outsider status in Sweden, while learning the language to fit in; and in America, her name and origins undoubtedly make her vulnerable in an escalating environment of hatred and fear of Muslims.

If Fontana’s cuts (or “tagli”) exposed the illusion of the surface in order to touch the spiritual void that lay beneath it, Kahraman’s cuts are metaphors of the body’s capacity to release psychic pain; and in mending the cuts, she becomes the cartographer of her own catharsis. Elaine Scarry has written extensively about the inexpressibility of physical pain, about the incommunicable nature of internal goings on that “may seem to have the remote character of some deep subterranean fact, belonging to an invisible geography that, however portentous, has no reality because it has not yet manifested itself on the visible surface of the earth.” The same can be said of psychic pain.

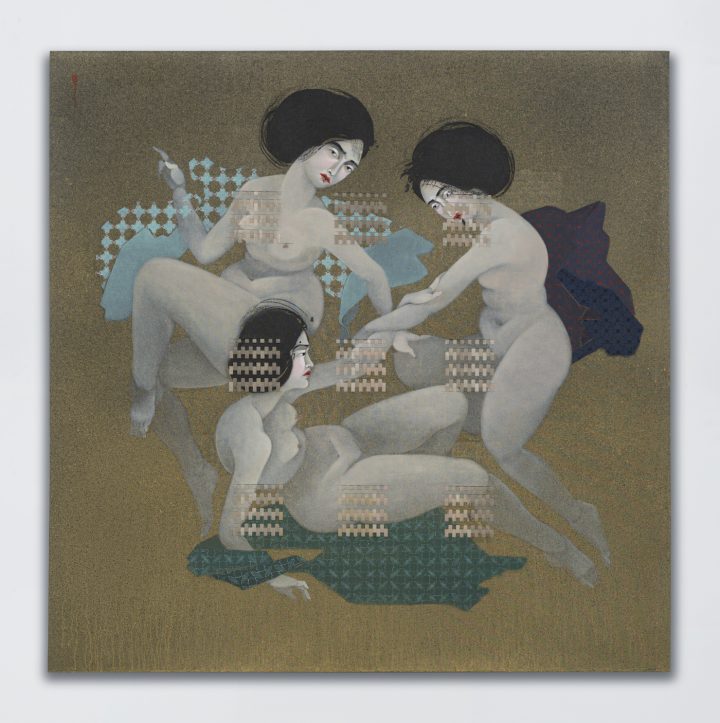

I think of the difficulty of locating pain as I view the six large paintings from Kahraman’s Mnemonic Artifact (all in 2017) series at Shainman. The weave appears as delicate longitudinal and latitudinal lines placed along the axes of diaphanous bodies, mostly nude, gathered in crowds, organized in single file or intertwined, as if dancing. The cultural signifiers denoting Kahraman’s ethnic heritage are sparse, and few – a colorful shawl with decorative motif patterns, ostensibly from pre-modern Iraq, and thick, jet black tresses and eyebrows set against pallid skin. While such features can arguably be attributed to her roots, the artist’s affiliation to multiple geographies allows her to traverse cultural anomalies with ease.

Rupture, slippage and assimilation are foundational to Kahraman’s methods and means. Her work imparts visual pleasure, but internalizes the migrant’s struggles for autonomy and freedom.

Kahraman’s mysterious creatures may reside behind a resolute mask, their idealized bodies offset by an adolescent brooding that keeps them safely tucked away (or are they trapped?) in a world we cannot access. But, like her, they refuse to be neatly trundled into fixed positions within the Orient and the Occident. The artist’s implicit resistance to the neat binaries of racial and gendered stereotypes lies at the core of her identity politics, and is indeed, its strength.